Maps and Legends

How the multiverse of wine exploded from the pages of a pocket atlas

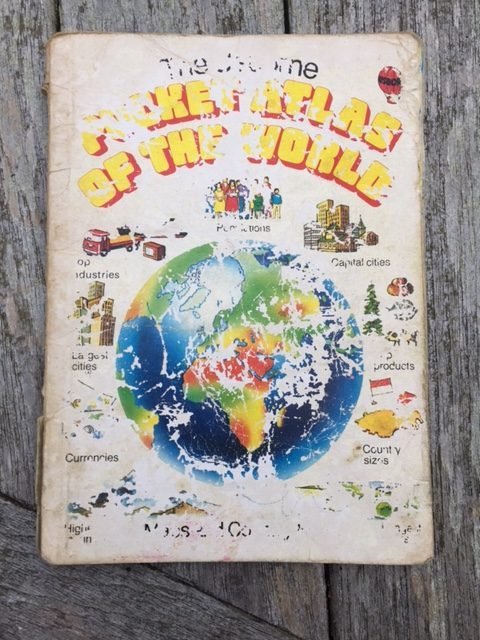

Don’t judge a book: My own Pocket Atlas of the World

It doesn’t look like much – a tatty little paperback with smudges of colour seeping through the grazes of its cover – but there’s perhaps no book that’s had a greater influence on my life. It was a Big Bang moment when the Usborne Pocket Atlas of the World turned up in my Christmas stocking as a kid in England. There and then, the universe unfolded into infinity. My imagination exploded.

It had all the usual headline stuff – continents, oceans, countries and capitals – but what really got me were the details. After the depiction of each region, there was a double-page spread on its currencies, populations, largest cities, industries and products. The diversity made me dizzy. All those languages and currencies. Pre-Euro, Europe alone was swimming in exotic money – francs, marks, pesetas, escudos and lire. The facts on industries and products were particularly evocative. It was somehow refreshing that the USA – which seemed to have the 1980s in its pocket – was actually not number one in everything. Bigger and wealthier than Brazil, but the latter had way more sugar and coffee. (No mention of wine there, though. That was France.)

Some lessons from the book:

1. The world is massive

2. There are many differences

3. These are interesting

4. Different places grow and make different things

5. There is more than one way to be ‘rich’

6. I gotta see some of this for myself

Simple points, but they sank in deep. I read Modern Languages at university, cycled round the world and became a journalist. These days I live by the beach on the Mornington Peninsula with my Australian wife (she wishes I hadn’t learnt point 5), spent almost a decade with one of Australia’s great wine importers and have started a business that aspires to ignite - and satisfy - in others a curiosity about wine.

Back in 2016, I completed my WSET Diploma with an overall distinction, a mark achieved by less than 1% of those who enrol worldwide. It took a fair bit of effort, and the relief on getting across the finishing line inspired my to pen this post.

The Diploma is the fourth and final level of a global course run by the London-based Wine & Spirit Education Trust. The course covers every aspect of wine in its still, sparkling and fortified guises – from viticulture and winemaking to business and culture, with most exams split into a tasting and theory component. It’s thorough and demanding. Not hard exactly, in that students are not set up to fail; if you do the work, you should go OK. But it’s the work that’s the hard bit.

From where I live amid sea and vines, it was more than an hour’s drive to the city where I was working most days. The question of how to cover the hours of study on top of full-time work and full-on family (a six-, four- and one-year-old when I started the course in 2014) had to be solved somehow. The only way was to breathe life into the dead time of commuting.

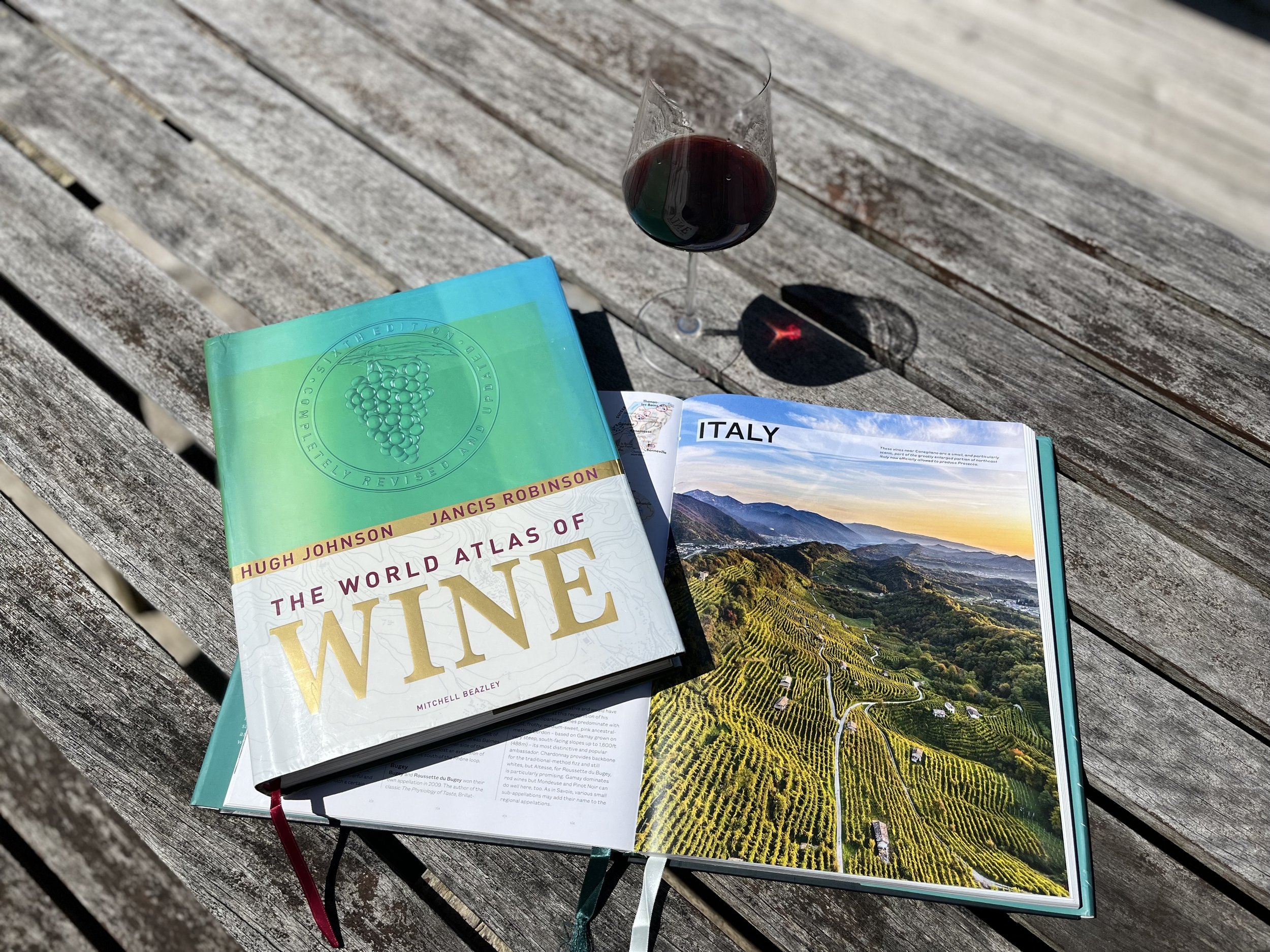

The World Atlas of Wine editions 6 and 8.

Late at night I’d record myself reading the key texts, then play them back in the car next day. My basic, bloody-minded method was to start with the course book, back it up with the corresponding pages of The World Atlas of Wine, and then hammer the points home with the Oxford Companion to Wine. I made no attempt to jazz up my presentation; it was about ploughing through. On an on I’d trudge through heavy yawns and the stumbling of a torpid tongue. More than once I fell asleep, map in hand, another lost explorer defeated by exhaustion.

The revelation came in the car. The course book itself is dry as the most mouth-sucking Chablis (but nothing like as palatable). Every time I hit a passage from the atlas, however, the pace picks up and the flat-lining delivery jolts into peaks and troughs. It’s the invigorating force of passionate, purposeful prose.

“Certain wines have within them a natural vigour, an inbuilt eloquence, that expresses as nothing else does the forces that made them,” writes English wine writer Hugh Johnson in his foreword. “You cannot trace a strawberry to a field, or a fish to a stream, or a gem to a mine, in the act of enjoying it. It is possible with wine, and not only to the place where it was made, and to the fruit that gave it flavour, but to the year the fruit ripened and even to the vintner who conducted operations. Does anything else so fully justify an atlas of its origins?”

Without doubt the aptness of an atlas to tell wine’s story is part of it. But listen again to the cadence of Johnson’s sentence, its articulacy and sheer good sense, and you see why he and co-author Jancis Robinson are such brilliant guides on a tour of the world of wine.

They transformed the freeway into the Rhône, the Rhine, the Danube and the Douro. Towering above me were the Mayacamas, the Vosges, the Hottentots Holland and the hill of Corton. You see the sights and hear how geography, geology, topography and climate intertwine. History and tradition are seamlessly woven into every tapestry. Fortunes rise and fall, pioneers are praised and the odd admonishment is dished out. Thus Germany is chided for confusing people and Italy for its leniency towards “dreary” Trebbiano Toscano.

They transformed the freeway into the Rhône, the Rhine, the Danube and the Douro. Towering above me were the Mayacamas, the Vosges, the Hottentots Holland and the hill of Corton. You see the sights and hear how geography, geology, topography and climate intertwine. History and tradition are seamlessly woven into every tapestry. Fortunes rise and fall, pioneers are praised and the odd admonishment is dished out. Thus Germany is chided for confusing people and Italy for its leniency towards “dreary” Trebbiano Toscano.

The writing is rich and respectful, precise but not stiff. It’s inviting, flinging open its doors and impelling you to stay. Always authoritative, it wears its learning lightly.

“The element you will find missing from this book, for lack of space, is an attempt to describe the beauty of its prime subject,” writes Johnson in his foreword. It’s one of the few things I disagree with. Take this, for instance: “In one of the marriages of grape and ground the French regard as mystical, in Beaujolais’ sandy clay over granite the Gamay grape, undistinguished virtually everywhere else, can produce uniquely fresh, vivid, fruity, light but infinitely swallowable wine. Gouleyant is the French word for the way fine Beaujolais slips ineffably down the throat.” Or, on Middle Mosel Riesling: “The greatest of them, long-lived, pale gold, piquant, frivolous yet profound, are wines that beg to be compared with music or poetry.”

This is the kind of nourishing sentiment that prevents the intense, gruelling nature of study from sucking the fun out of wine. Like the best hosts – and the humble winegrowers who entreat you to drink deep from their well of hard-won wisdom – the authors of The World Atlas of Wine make you feel utterly at home no matter where in the world you are. I’m grateful to them for carrying me on their fluent, cultured tide to the latest port on my journey.

Anyway, it’s almost time for a glass of wine. I wonder what to have? “There is a sad segment who never want to pay more than the minimum for their drink, or indeed their food. Battery chickens were invented for them – and indeed battery wines,” writes Johnson. “For those who travel, though, those who eat out, cook, and share pleasures with friends, it is choices that matter: the choices between flavours and cultures.”

When I think of that dog-eared atlas from all those years ago… What choices it inspired!